According to the National Geographic Society, “in 1984, the National Council of Geographic Education (NCGE) and the Association of American Geographers (AAG) broke the discipline of geography into five major themes, which some continue to use to help teach geography: location, place, human-environment interaction, movement, and region.”

When I think about my hometown of St. Joseph, Missouri, four of those terms are easy to define. “Location” would be its map coordinates: 39°45'29"N, 94°50'12"W. “Human-environment interaction” might be how, like everywhere, builders have turned farmland into suburbs, or how residents still cherish their Parkway system, largely shielded from development since the 1920s. “Movement” is easy to document, both in the town’s growth in the 1800s as a jumping-off-point to the American West and through people’s migrations within and around the city. “Region” can be Northwest Missouri or Lower Missouri Velley.

But “the concept of place” is where the fun starts.

Again, according to National Geographic: “Sense of place is the emotions someone attaches to an area based on their experiences.”

My earliest emotional attachments to St. Joseph start not in the city itself, but half an hour to the east. That’s because, before anything else, and after nothing else, I remember my mom hanging laundry on the line outside of our soft-pink, two-bedroom ranch in Cameron, Missouri.

The air is clean and damp and warm. A broad expanse of green grass spreads before us, beads of dew sparkling in the climbing sun. I am looking to the west, toward St. Joseph, where my family would move in April 1968. I wouldn’t have been two years old yet.

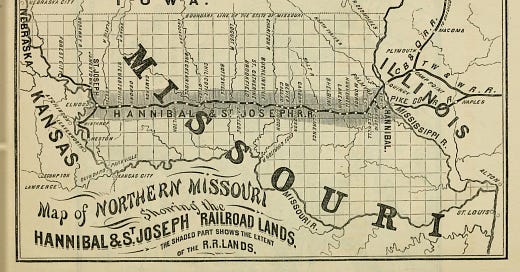

The Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad originally linked Cameron (founded 1854) to St. Joseph (1843). The rail line crossed the state, from Hannibal on the Mississippi River to St. Joseph on the Missouri. The tracks ran through the center of Cameron, and the old depot still stands there, as a museum.

Today, I imagine farmers bringing their crops to town for shipping to the east or west. But by the time we moved to Cameron, another link between Cameron, St. Joseph, and Hannibal had emerged—a two-lane state highway, U.S. Route 36. It opened in 1922 as Route 8, following the route of an old covered-wagon trail and, probably, a Native American trade route before that.

Route 36 brought my parents to Cameron in November 1963 just a month after my dad had gotten out of the Army. A civil engineer, he had begun working for the Missouri Highway Department in Savannah, a small town just north of St. Joseph, before enlisting. He came to Cameron to resume his career with the highway department, and his first job was to help build bridges for Route 36 over the new Interstate 35, heading north from Kansas City to Des Moines, Iowa.

My dad and I took a field trip to Cameron a few years ago. He remembered that one job involved a bridge that required a 1,082-foot box culvert that took 26 separate pours of concrete. But almost all I remember about Cameron is watching mom hang laundry.

When we arrived in St. Joseph in the spring of ’68, we moved into another rental on a street called Trevilian Drive. The street, just a quarter of a mile long, began and ended on the Belt Highway, creating an ellipse of earth bordered by Trevilian and the Belt.

Closer to the south end of the ellipse was our house. On the north end, where Trevilian rejoined the highways, sat the farm home where Robert Ford had shot the outlaw Jesse James to death, striking him in the back of the head as he straightened a picture. The home had been moved from another location in town to be a tourist attraction on the busy Belt Highway, and for 50 cents visitors could walk through the house and stick their fingers in the bullet hole, before it was framed behind glass.

Just a mile or so north of the James Home was the Pony Express Motel. Another tourist draw, it featured a neon sign out front depicting a Pony Express rider departing from St. Joseph on April 3, 1860, to carry mail from the city to Sacramento, California, 2,000 miles away. On the sign, the rider’s horse pumped his legs in pulsing red neon.

A street possibly named for “the largest all-Calvary battle of the Civil War.” A house where a criminal and Confederate guerrilla had been killed. The Pony Express. And our little Trevilian Drive house, where we would live for the next two years.

I’m not sure what to make my young proximity to these 19-century events, connected like towns on a railroad map. After we moved from Trevilian Drive, we lived along the Parkway, which had more of a vibe of early 20th century, Progressive urban planning feel, plus a lot more greenspace, trees, and even a creek.

Still, I always felt that 19th-century burden weighing on me, a past of violence and faded glory, muted by the broken promise that clinging to that past—which did fascinate me—would return prosperity to the tired town. The past was always there, as inescapable as a bully on the schoolyard, even if so many of my St. Joseph days were as charmed as that spring morning in Cameron, watching my mom hang laundry in sun.

It is interesting to think how time and people can change a person’s perception of a place. I have no nostalgia for Cameron. I never lived there even though we grew up in the same family. But I do have similar fond memories of the same woman hanging laundry outside in the warm, fresh, crisp breeze of St. Joseph. And the house on Trevillian drive feels more like a museum to me; a place attached to me only for its relevance to the past as a place where my family once lived before I was born. Where people significant to me probably once hung pictures.

My geographer's heart loves your framework and how beautifully you captured what place can mean! ❤️